Joaquin Flores

For Netanyahu a compliant Venezuelan government could represent leverage against parts of the various integration frameworks that don't work for him.

Why has the U.S. Navy assumed a threatening posture against Venezuela without attacking it directly? To answer this, we have to look in some surprisingly unsurprising places. Let's start with last October. It could not have gone unnoticed that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was among the very first to personally congratulate Venezuelan opposition figure María Corina Machado for winning the Nobel Peace Prize. There are really only two other major national leaders that would follow suit: Milei in Argentina and Merz in Germany. Both have been noted for their uncritical alignment with Likud politics and Israel's war in Gaza, and indeed stand out for it. Why was Machado so uniquely praised by this trio?

The official line is that Machado will purge hidden Iranian backed Lebanese Hezbollah cells from the jungles of Venezuela, but few adults in the room take this seriously. It is almost insulting, truly a stretch to believe, and reads like a poorly scripted Hollywood B‑movie from the 1980s. Netanyahu's interest in Venezuela instead likely centers on oil and Israel's need to diversify energy sources, while gaining leverage over Gaza should he challenge the ceasefire and UN Security Council Resolution 2803, even at the risk of regional economic normalization. Showing alternatives like Venezuela gives Israel flexibility to pressure a derailment of Gaza peace even if current oil supplies are cut because of political fallout from suppliers. Is Trump aligned with Netanyahu's strategy, or is something else driving it?

Venezuela holds the world's largest proven oil reserves, approximately 303 billion barrels as of 2024, surpassing even Saudi Arabia. During her interview with Donald Trump Jr ., Machado emphasized that Venezuela's reserves were larger than Saudi Arabia's and spoke in remarkably colonial terms about opening Venezuelan oil to unlimited exploitation by American interests. Did she really only mean American? Perhaps an understanding of the Venezuelan situation requires that we understand Netanyahu, Trump, and MbS's ongoing tension on Gaza peace and normalization.

Israel's Limited Options: Two choices

Israel has two main strategies moving forward in economy, energy, and security. It can rely on Europe and Western support or integrate into the regional economy. The first maintains the old regional orientation but is economically inefficient. Without new sources like Venezuela, Israel risks stagnation while regional partners advance, giving Saudis excessive leverage. This is precisely why Tel Aviv has pursued IMEC and normalization. Access to low-cost Venezuelan oil could delay this or strengthen Israel's negotiating position.

The second strategy requires committing to regional economic integration, expanding the Abraham Accords, and normalizing with Saudi Arabia, which is preferable to Israel on the whole. It strengthens existing Western ties, but its obviousness weakens Netanyahu's bargaining position and forces a politically risky path domestically, alienating extremists who view Gaza as part of Israel for settlement and annexation.

IMEC and the Saudi angle

To secure a strategic position as a transit hub and access part of Saudi oil, Israel plans to seek better pricing and mechanisms than its current suppliers provide. Israel recognizes that its regional orientation must change, especially with Saudi Arabia. Riyadh will not normalize with Israel or join the Abraham Accords without Gaza peace and redevelopment, in line with its long-standing 2002 Arab Peace Initiative, which now depends on the success of Trump's 20-point plan.

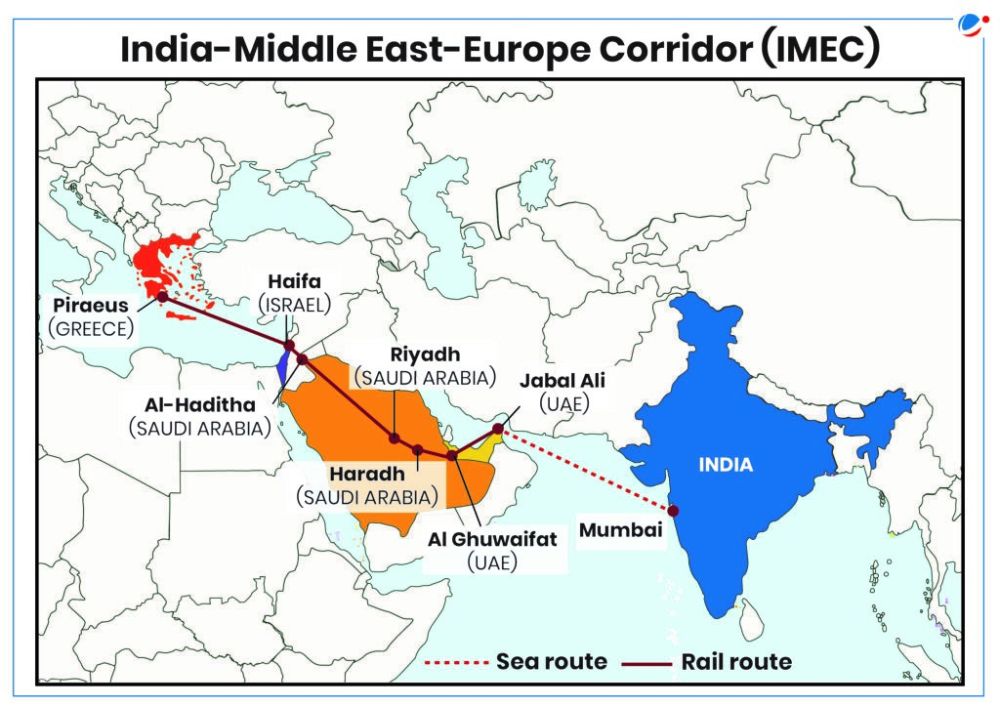

Israel has proposed a direct oil route from Saudi Arabia to Europe via its territory, according to statements from Minister Eli Cohen. The plan calls for a 700-kilometer pipeline to Eilat, then onward to Ashkelon via the Eilat‑Ashkelon Pipeline Company (EAPC) (also called the "Europe‑Asia Pipeline"), and finally through the Mediterranean via Cyprus and Greece to European markets. Cohen framed it as a way to expand the Abraham Accords and bolster Israel's strategic and economic position in the region, but of course relies upon normalization with Saudi Arabia which the IDF invasion of Gaza worked strongly against. The broader agreement is a large feature of the IMEC project (the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor), which Israel has a love-hate relationship with.

The Abraham Accords for Israel ideally would have resulted in normalization and Israel proceeding as the primary hub of goods from India, oil and natural gas exports from the Mid-East region, destined for Europe as part of the IMEC project. But the Saudis are not on board with normalization unless Israel 'gives up' Gaza, so IMEC will not work unless Netanyahu adheres to the 20 point plan. Both Israel and Saudi Arabia want IMEC, but only the Saudis are geographically contingent. Israel's role certainly comports with India's relationship: it is desirable for India yet is not fundamental if it comes down to bypassing obstacles obstructing Indian goods from reaching Europe.

IMEC infographic credit: www.imec.international

Israel sees IMEC as central to its economic and strategic position, but the corridor's design is not entirely under its control. The Gulf States, especially Saudi Arabia, could choose to route energy exports through Gaza rather than Israel, effectively making Israel an afterthought. In that scenario, pipelines and transit infrastructure could bypass Israeli territory, leaving Israel with far less leverage over energy flows and regional trade. This possibility underscores that Israel's benefits from IMEC are contingent on Gulf cooperation and on concessions regarding Gaza and Palestinian normalization.

Had the IDF succeeded militarily and politically in Gaza and ethnically cleansed the Palestinians, then Gaza would be de facto Israeli territory, and Gaza as an alternative hub independent of Israel would be off the table. Maybe this much explains part of Netanyahu's gambit in that failed war of conquest.

The Saudis may also have another option yet. In the past, the Saudis had an oil line directly to Lebanon. TAPLINE began operation in 1950, carrying Saudi crude across Jordan and Syria into Lebanon for Mediterranean export, and for a short while it promised to reorder the political economy of the Levant. It was built by the American companies that controlled Aramco at the time, and the point was to export Saudi oil to the Mediterranean without shipping tankers through the Suez Canal.

But Syria cut the pipeline during the 1967 war to punish Saudi Arabia for its ties to the U.S. This shut the Syrian segment, crippling the entire line. But the change in Syria's government recently changes that metric.

TAPLINE route in the 1950s

The problem that Israel faces with either importing Saudi oil in the future, or with maintaining its present network of suppliers, is the same: backtracking on Gaza peace and re-engaging in hostilities will stop Saudi plans from materialize and likely cause Brazilian and Turkish hesitations to manifest more fully into significant reductions, even stoppages.

Israel's war in Gaza is a real thorn in the side of IMEC. Analysts say the Gaza conflict undermines the corridor's viability by 'arresting normalization talks' between Israel and the Saudis.

Venezuela works for Trump already

Maybe Trump has an interest in regime change in Venezuela. Maybe he doesn't. It is difficult to justify it from a cost-benefit perspective, or when considering that the present arrangement works quite nicely for Trump. Chevron already operates profitably at five Venezuela locations under the current Maduro government, being 30%-40% partners with PdVSA. Certain sanctions limitations were paused courtesy of Treasury Department OFAC exemptions issued over the summer and as late as August 2025 by the Trump administration, allowing business to continue. The apparent general alignment between Maduro and Trump in the present geopolitical moment was the foundation of our piece " Are Trump and Maduro secretly friends? Smoke & mirrors in 47's win-win game in Venezuela", which delves into important background.

There is another angle that is impossible to ignore. Venezuela is already functioning in a way that suits Washington perfectly. By turning Caracas into a public villain, the United States masks what is, in practice, a workable arrangement. At the moment, only the U.S. can buy Venezuelan crude at normal pricing, and even then it effectively receives an additional discount because all of the transaction is settled in refined products credited to Venezuela at retail value. Everyone else pays a heavy premium. Any non-U.S. buyer faces a twenty-five percent tariff on top of whatever tariffs regime happens to be in force. The net effect is to turn Venezuela into a kind of de facto private reserve for the United States, both cheaper and more secure for Washington than the drama in the headlines would indicate.

The following offers additional support.

According to Venezuela Analysis in early August:

"U.S. oil company Chevron is set to restart crude shipments from its joint ventures in Venezuela under a renewed U.S. Treasury sanctions waiver, Chevron CEO Mike Wirth confirmed Friday[...]

'This month, it looks like there will be a limited amount of oil that will begin flowing to the U.S. from the Venezuela operations that we have an interest in,' [...]

The oil executive added that the restart of oil drilling and export operations in Venezuela would have a limited short-term impact on Chevron's profits but would help the firm begin recouping debts. Wirth, who had extensively lobbied the Donald Trump administration to continue its activities in Venezuela, reiterated the corporation's commitment to comply with U.S. sanctions.

Anonymous sources recently confirmed to Reuters that the specific license had been issued following earlier reports. Unlike general licenses, specific ones are handed directly to companies and not published by the U.S. Treasury Department."

Bloomberg reported recently in a piece on Chevron's Mike Wirth that "Chevron Corp., the only major U.S. oil company left in Venezuela, wants to remain in the sanctioned country for the long-term and sees a role in rebuilding its economy when the time is right." This kind of ambiguity does not commit Chevron to any outcome while also plainly saying they plan to continue to operate there now for the time being.

ExxonMobil elected not to operate in Venezuela sometime after Caracas enacted nationalization reforms some decades back, but they could probably return. The U.S. at any time could simply decide to lift sanctions on Venezuela, but doing so would require navigating prices and OPEC politics.

Venezuelan crude restricted by sanctions tends to support higher prices per barrel globally. Saudi Arabia, as the largest OPEC producer with flexible spare capacity, benefits from the present arrangement because it can sell more crude at elevated prices without losing market share. In short, U.S. sanctions on Venezuela indirectly strengthen U.S. and Saudi revenues and market influence as they limit total volume, while also giving Riyadh leverage within OPEC to manage production and prices.

The context here is key: Venezuela produces roughly 900,000 bpd, while Saudi Arabia produces about 9 million bpd, meaning that Venezuela only produces 10% of Saudi output. A full Venezuelan return to the market would cause global price cuts and work financially against oil exporting countries like the Saudis and the U.S., which exports about 4 million bpd of the 13.5 million that it produces.

Trump may still believe he can reshape Venezuela's political structure or increase Chevron's share in its joint venture with PdVSA and potentially bring ExxonMobil back. Maduro appears willing to cooperate. But U.S. energy companies already have access, and sanctions can be lifted at Washington's discretion. Venezuela continues to hold dollars and conduct most of its oil trade in USD, with sales totaling $17.5 billion in 2024. What extra value would regime change bring? Without kinetic U.S. involvement, it is unlikely to succeed, and an overt attack would devastate oil infrastructure while entangling the U.S. in risky troop commitments. Chevron is not pushing for regime change; pragmatically, it prefers trade and business over sanctions, threats, or war.

In fact, U.S. imports of Venezuelan oil have risen in 2025, reaching about 250,000 barrels per day in January, some of the highest levels since sanctions began in 2019, and tanker‑tracking data show exports hitting a nine‑month high in August, with roughly 60,000 barrels per day going to the U.S. Gulf Coast. This increase is driven largely by Chevron's resumption of operations under a U.S. license, confirming a direct link between Venezuelan supply and U.S. refineries, with the U.S. receiving 37% of all of Venezuela's crude.

In retrospect, maybe things are more or less reliable just as they are; prices are stable and the Saudis seem content. Venezuela is able to receive remuneration in kind provided it is non-transactional from the joint venture, with CNN indicating in a report that this was given in terms of barrels;

"In July, the Trump administration renegotiated a license authorizing Chevron, a major U.S. oil company, to export Venezuelan crude. Under the new terms of the license, Chevron was authorized to pay fees and royalties to Venezuela in oil but not in cash, effectively reducing Chevron's crude exports from the country by half, according to Reuters."

So far, Trump's naval buildup and the desirability for regime change in Caracas don't seem to add up. The American side and oil producing countries seem okay with the present Venezuelan situation; even Caracas prefers it over war or regime change. What else can be at play?

Towards a conclusion

For Netanyahu a compliant Venezuelan government could represent leverage against parts of the various integration frameworks that don't work for him, at least giving him the appearance of plausible future options.

Israel's dependence on oil that passes through Turkey comes from Azerbaijan, through Russia from Kazakhstan, or from Brazil, are jeopardized by Netanyahu's bellicose impulse towards Gaza, and in addition Israel has a strategic mandate for energy. We plan to review some evidence that Turkey already has taken action. Part II will take those strands and lay out the real mechanics of Israel's energy profile, and why those channels limit Netanyahu's political room on Gaza, and why a steady stream of Venezuelan heavy crude under a special arrangement with Machado would solve problems the United States has no incentive to solve, and to the contrary appears to be pushing against.

Details of Machado's understanding with Netanyahu will be a focus in our next installment, and with it the logic behind the recent U.S. naval posture toward Venezuela, including the odd redeployments away from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Persian Gulf. Opening Venezuela to Israel through a U.S. engineered transition in Caracas would undercut Trump's own Gaza development plans if it hands Israel a credible alternative path, yet the carrier group continues to hover just over the horizon.