Revived during the Saudi Crown Prince's visit to Washington, the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor promises to reroute global trade away from the Suez and from China. Experts warn that missing funding, Brussels' own green taxes, and regional wars could bury the project's bolder ambitions.

Friday, December 5, 2025

Uriel Araujo, Anthropology PhD, is a social scientist specializing in ethnic and religious conflicts, with extensive research on geopolitical dynamics and cultural interactions.

The "revival" of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) has been curiously underreported, despite its geopolitical claims and grand rhetoric.

Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's (MBS) visit to Washington on November 18-22 has once again placed the project on the diplomatic agenda. As Afaq Hussain (a Non-Resident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council) notes, "the MBS visit to the White House could revive IMEC," framing it as part of a broader rapprochement between Riyadh and Washington and a renewed push for "regional connectivity".

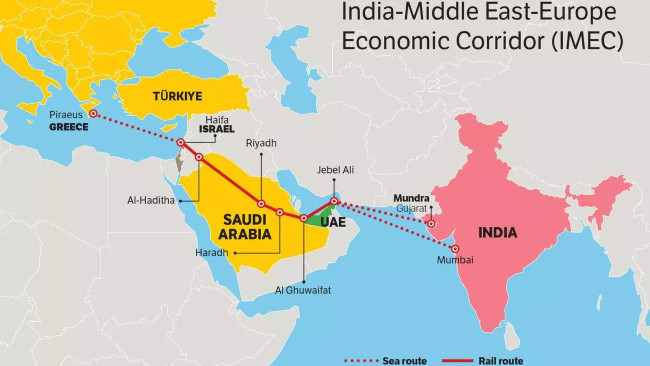

Announced with some fanfare at the G-20 Summit in New Delhi back in 2023, IMEC has been pitched as a transformative trade route linking Indian ports to Europe via the Gulf and Israel. It would connect western India to the UAE by sea, cross Saudi Arabia and Jordan via rail, and exit through the Israeli port of Haifa to Greece, Italy and France. It was hailed by Trump earlier this year as "one of the greatest trade routes in history."

Afaq Hussain summarized the logic behind this: the Corridor has been marketed as an alternative to the Red Sea and Suez routes, which have become vulnerable chokepoints amid instability, and as a pillar of Saudi Arabia's ambition to reinvent itself as a global logistics hub. Shortly after its announcement, however, the Gaza war froze political engagement between Israel and Arab states, leaving IMEC suspended in diplomatic limbo. Now it is supposedly back.

The West presents IMEC as a commercial infrastructure plan. But no project of this scale is ever just infrastructure. As a matter of fact, it is, quite plainly, also a geopolitical instrument aimed at realigning India westward, embedding the Gulf into European supply chains, and countering China's Belt and Road Initiative ( BRI). That much is clear enough.

No wonder the G-7 and the EU have embraced it rhetorically. For Europe, IMEC promises resilience: shorter routes, diversified energy flows, and distance from politically sensitive corridors. For Washington, the Corridor is a strategic lever to strengthen India's Western orientation without forcing Delhi into overt alliances.

For India and key Gulf partners, the carrot is obvious. Hessa Abdulla Al Nuaimi (Assistant Researcher at TRENDS Research & Advisory) notes that India has already committed to a $9 billion deep-water port at Vadhavan, while AM Green is developing a $1 billion green fuel corridor with Rotterdam. Al Nuaimi emphasizes that Europe is increasingly positioning India as a supply-chain alternative to China, while the Gulf states perceive IMEC as a way to cement their roles as indispensable transit powers. In her words, the corridor is not just about connectivity but about "resilience and competitiveness in a changing global order." Be as it may, vision in itself is not execution.

For one thing, the European Union's own policies already contradict the corridor's economic promise. In fact, the EU Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) penalizes imports based on carbon intensity. Indian exports embody higher emissions, meaning that goods shipped faster via IMEC could still be priced out of European markets. This being so, unless CBAM is paused or adjusted, the corridor's energy dimension would suffer from policy sabotage from Brussels itself.

The financing picture in turn is not really reassuring. China launched BRI with state banks, sovereign underwriting and centralized coordination. IMEC, in contrast, has none of that. There is no unified authority, no multilateral funding structure, and no binding commitments: investment is fragmented, conditional and politically sensitive.

As researcher Wina G.S. Simanjuntak, writing for Modern Diplomacy puts it: "IMEC's fundamental mistake is treating infrastructure primarily as a geopolitical statement rather than an economic necessity." Unlike China, which built first and preached later, IMEC launched with press conferences and hoped the capital would follow. But it faces financial uncertainties about costs, amid several problems. "Unless fundamental issues of financing, security, and coordination are resolved," Simanjuntak writes, IMEC will remain "an idea on paper".

Security might be the silent killer of the project. The Corridor runs through Gaza's periphery, the Red Sea war zone, Saudi territory, and the fractured Eastern Mediterranean. A corridor is only as reliable as its weakest border. And IMEC has many such borders.

Digital integration, often cited as its modern edge, is also more complicated than advertised. Elizabeth Heyes, a Technology Junior Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation (ORF) Middle East, acknowledges that "physical digital infrastructure" is being discussed but warns that interoperability depends on harmonizing customs data, privacy laws, and technical systems across incompatible bureaucracies. In fact, a single functioning platform between India and the UAE is promising but not scalable by default.

China funded, built and operated railways in Central Asia, ports in Africa, highways in Pakistan and power plants across Southeast Asia. It is unclear to what extent the Economic Corridor may be an "alternative". The West wants it to do many things at once: re-anchor India, hedge China, integrate the Gulf, bypass Russia, decarbonize Europe and stabilize the Middle East. That is, of course, a lot to ask of one railway line and a few cables.

Ambitious enough a project as it is, it lacks institutionalizing and faces strategic and financial issues. The corridor may indeed deepen bilateral investment, expand Gulf-India trade, and generate projects on its margins, but it is hard to imagine how it could really become a systemic alternative to Eurasian land routes or to BRI.

One may thus argue that IMEC, in a way, is a geopolitical gesture dressed as a logistics revolution. That, to be fair, does not mean it will fail; it means it is not necessarily what its champions claim. It might be a hedge, but it is not a replacement; and most likely not a new Silk Road.