they say that breaking up is hard to do -

Blockbuster report calls for beefing up enforcement and aiming for breakups.

Kate Cox - Oct 7, 2020 8:16 pm UTC

Google: It's a lot of bad behavior

Google's position as the dominant search engine is well-cemented. But over the past 20 years, the company has shifted its behavior "to rank search results based on what is best for Google, rather than what is best for search users," the report concludes, "be it preferencing its own vertical sites or allocating more space for ads."

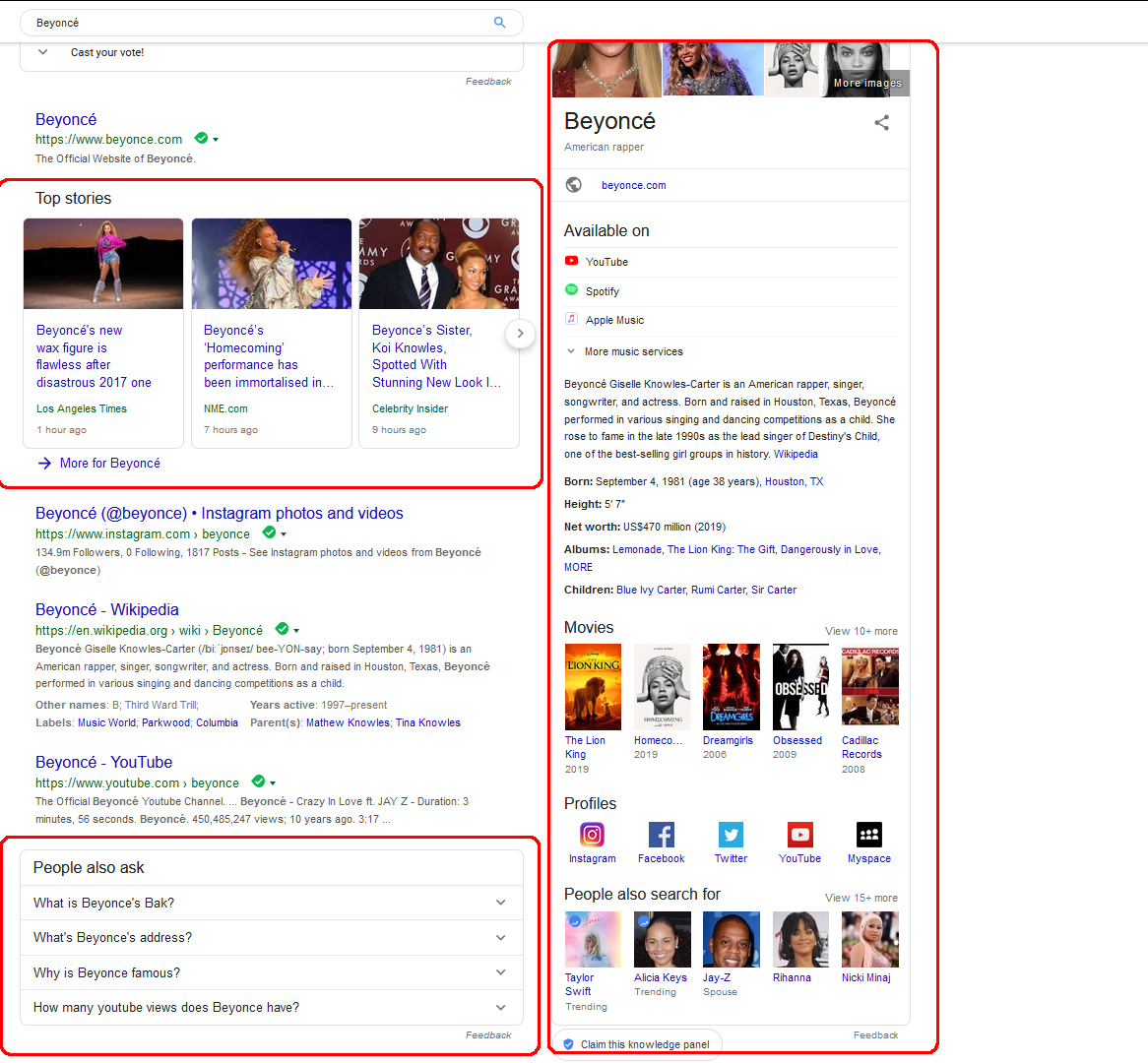

The best way to demonstrate how much Google content shows up in a Google search is with an image, like so:

Enlarge / Most of the results on the page are Google modules (highlighted in red).

As a result, Google users who search for information are no longer visiting non-Google sites to reach that information. Instead, they are confronted with a wall of Google modules and advertisements. One advertiser told the committee that Google "effectively forces its advertising customers to pay for the ability to reach consumers who are searching specifically for the customer's brand," adding that since there's almost no real competition in search, "Google has the ability to charge potentially inflated prices for its advertising services by forcing customers to increase their bids in order to receive a more favorable position."

Google-or rather, its parent company, Alphabet-makes more than 80 percent of its revenue through the advertising business. It is able to maintain its position as the Internet's biggest display advertiser because it controls so many links up and down the chain, one witness told the committee:

Google is now not only a seller and broker of digital advertising across the Internet, but they now also control significant portions of the web browsers, operating systems, and platforms upon which these digital ads are delivered. This gives Google the ability to single-handedly shift an entire ecosystem in nearly any direction they decide, based simply on their scale. Google can then use its dominance to demand a higher share of ad revenues from buyers and sellers, and there is little leverage available to counteract this position in a negotiation.

Google, like Facebook, came to its dominance through acquisitions. First, in 2007, it paid $3.1 billion to acquire DoubleClick. Then, in 2010, it snapped up mobile advertising platform AdMob, and in 2011, it acquired AdMeld. Each of those three transactions individually passed muster; taken together, however, they add up to massive dominance in the market. Google also promised at the time of the DoubleClick acquisition that it would not combine consumer data acquired through DoubleClick with data it acquired through its other properties; in 2016, however, it abandoned that promise and assembled a data juggernaut.

The committee also found that Google extended its long reach into Android anticompetitively by bundling in and giving preference to many other Google features, especially including Google Search. The company's strategy of licensing Android for free but "conditioning access to Google's must-have apps on favorable treatment for Google Search" allowed the company successfully to block out rivals. (European regulators fined Google $5 billion for similar behavior in 2018.)

The entire intertwined Google ecosystem comes back together into one big maelstrom of data abuse, the committee concluded, particularly when it comes to Chrome, Google Maps, and Gmail.

So now what?

The committee cannot actually take action against any of the companies. Antitrust oversight falls to the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice-and the report has strong recommendations for both. It also suggests, going forward, the ways that Congress can amend antitrust law both to ameliorate the current problems and prevent future ones.

Reduce conflicts of interest through structural separations and line of business restrictions

That's a lot of words to say something very simple: these companies need to be split up. Dominant platforms, the report concludes, are exploiting their integration, tying products and services together anticompetitively while exploiting that dominance to squeeze profits out of would-be competitors. How do you fix that? By un-integrating them.

Implement rules to prevent discrimination, favoritism, and self-preferencing

There's no law against systematically preferencing your own content above third parties'content, because antitrust laws were written before anyone knew that digital content was a thing that could have a dollar value attached to it. Congress, the committee concludes, needs to consider bills that would mandate nondiscrimination. If that reminds you of net neutrality, you're not wrong; the report cites the FCC's now-defunct 2015 Open Internet Order as an example.

Promote innovation through interoperability and open access

If a firm has data locked up, customers don't think they can switch away, and competitors can't access the same playing field. If that data becomes accessible, it becomes harder to abuse anticompetitively. The EU is also considering a law that would mandate data interoperability among platforms.

Reduce market power through merger presumptions

As of right now, legally speaking, mergers are assumed to be harmless unless regulators leap in and prove otherwise. The committee proposes switching the burden of proof: acquisitions by dominant platforms would be assumed to be anticompetitive until the merging parties can prove otherwise.

Strengthening the antitrust laws

Antitrust enforcement in the United States has fallen off precipitously since roughly 1980. Court rulings over time have weakened existing statutes and made it difficult both for regulators and private parties to challenge anticompetitive conduct in court. So, the report concludes, we need to strengthen antitrust law to broaden the theories of harm regulators use to make merger determinations. And in that vein, the report also recommends "invigorating" merger enforcement-i.e., putting a whole lot more time and money into it than regulatory agencies currently do.

Will that actually happen?

The answer is a giant "maybe" with a side of "it depends." Neither current presidential candidate-incumbent President Donald Trump or Democratic challenger Joe Biden-has clearly stated a policy platform to break up Big Tech. But both have expressed extreme frustration with the current state of tech, and either could end up supporting some portion of Congress's recommendations. Whoever becomes inaugurated in January 2021 as the next president will have the power to name the DOJ and FTC officials who are responsible for antitrust enforcement, and those nominations would strongly affect what happens next.

As for Congress, although bipartisan efforts are extremely difficult to come by, there is hope for at least some minimal common ground on antitrust. Rep. Ken Buck (R-Colo.), a member of the antitrust subcommittee, issued a statement indicating that although he does not agree with all of the report's recommendations, he and other Republican colleagues agree that the findings have merit.

"It's clear that the ball is in Congress'court," Buck said. "Companies like Apple, Amazon, Google, and Facebook have acted anticompetitively. We need to rise to the occasion to offer the American people a solution that promotes free and fair competition and ensures the free market operates in a free and fair manner long into the future." Several other Republican members of the committee signed on to similarly themed statements.

Page: 1 2

reader comments 278 with 131 posters participating, including story author