Joaquin Flores

Color revolutions are often misunderstood as either purely manufactured spectacles or purely organic eruptions of popular anger.

The Guardian ran a strikingly one-sided article in mid-December on the aftermath of the Gen Z 212 protests that swept Morocco months earlier, pushing the idea that rioters were young protesters and state repression was the sole story worth telling. The Gen Z protest label itself, a catchy and highly portable brand with a distinctly Sorosian Color Revolutionary feel, has traveled easily across borders, appearing in Mexico and Indonesia, even playing the main role in the toppling of the government in Nepal.

Color revolutions are often misunderstood as either purely manufactured spectacles or purely organic eruptions of popular anger, when in reality they typically sit at the intersection of real, observable frustrations but also a consciously constructed Baudrillardian hyperreality. What's most interesting about the Gen Z protests is that the implicit generational tension was expressed symbolically and implicitly by its branding, while explicitly attacking the corruption and methods of those in power who also happen to be older.

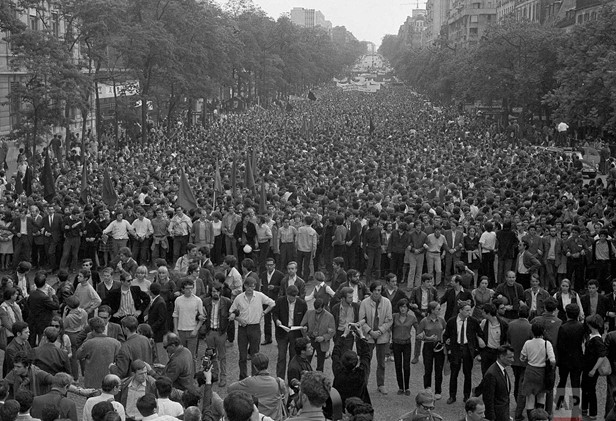

The color revolutionary potential of a purely generationally driven coup technique is difficult to ignore, because it is driven by a certain prejudice giving rise even to extremism, which governments and policy shapers have a difficult time countering. Governments have a mandate to deliver rational policy solutions. But if the underlying gerontocratic tendency of top governance in a society is at the root of the critique, it offers a condemnation of society which even pre-civilizational human tribal society cannot escape. An egalitarian polity would still tend to favor meritocratic decision making, with age being an obvious factor. The color revolutionary process of the so-called "student protests" underway in Serbia contains strong aspects of this, and while of a different time and flavor, this much is shared with the May of 1968 protests in Paris.

May 1968 - Paris (AP Photo)

Like many forms of managed social strife, "OK Boomer" intergenerational strife is simultaneously genuine and synthetic. Distinguishing between those elements is not only an academic exercise but a practical necessity, particularly from a security studies perspective where political planners and intelligence organizations need to understand what they are actually dealing with. In consulting players involved in countering color revolution pressures, there is a repeated encountering of a binary mindset among less experienced clientele: either the motivating themes are delusional inventions (which leads to overconfidence), or that they are wholly authentic and self-explanatory (leading to demoralization). The reality is more complex and yet also more useful.

Exporting the conflict-control model

What we are dealing with in this piece are two distinct applications in terms of domestic versus export models of this trope within color revolution technology, and also two different (though not mutually exclusive) arenas for change: long term and short term. Long term change can be affected by one country or bloc against another over several generations. These shape underlying cultural norms and attitudes that will create significant change over time, i.e. societal change. They also therefore shape the conventions, "common sense" of shorter-term projects like narrower theme, political, and contemporary issue driven protest movements which can topple governments, i.e. immediate political change.

Color revolutions and their methods, which we have developed in past work such as the July 2021 piece " Cuba and Color Revolution: A Cautionary Tale of the Next Phase of Forever-War", deconstruct how these revolutions are not single events or even limited-to-season plans, but long-game soft-power processes that reach deep into the consciousness of the population, often over years and, in the case of long-time targets for regime change like Ukraine, Russia or Serbia, for generations. Critically here we see that color revolutions are little more than the export of the same conflict-control techniques already used domestically by the states that promote them. This is the reshaping the target country into a post-modern illiberal polity which uses the ongoing social strife in their own society as part of its legitimating ideology, and the primary aspect which they export through the NGO industrial complex.

Divisive methods developed to control their own populations are repackaged and projected outward, aimed at capturing not only a foreign government but also the imagination, emotions, and political energy of its people.

Inter-generational conflict is one of these, and all of these.

American culture remains a strange and compelling thing to study, not least because its internal generational arguments often spill outward as they are modeled in soft power mechanisms in media and entertainment, and shape how the rest of the world imagines modern life, which also influences color revolutionary processes. Simultaneously many societies now modernize through technology while preserving their own culture, discovering that modernization does not require Westernization. Japan serves an excellent example, so much so that the primary meme/symbol for the Gen Z protests was from Japanese comics.

The familiar CANVAS-style organizations remain active, now funded more heavily through EU and UK grants and philanthropic networks and less visibly through USAID or the NED, even as Soros and similar donors continue to appear with considerable consistency. The state sponsors have shifted emphasis however, reflecting a broader reality in which American leadership in this space is waning, even as the machinery it built continues to operate within the context of declining transatlantic cooperation as a geopolitical reality.

Color revolutions generally attract younger generations more than older ones, but the Gen Z protests, even while the demands were not generationally specific (corruption, etc.) were attended overwhelmingly by gen Y and Z demographics, and the logo was selected to attract them. As CNN accounts:

"The flag comes from the wildly popular 1997 Japanese manga One Piece by Eciichiro Oda, which tells the swashbuckling story of the charming pirate captain Monkey D. Luffy and his misfit"Straw Hat"crew. Together, they set sail under a Jolly Roger flag that wears Luffy's quintessential straw hat and his trademark beaming smile.To One Piece fans, the flag symbolizes Luffy's quest to chase his dreams, liberate oppressed people, and fight the autocratic World Government."

Protest in front of the governor's residence in Surabaya, Indonesia on August 29. Juni Kriswanto/AFP/Getty Images

There is some debate then over how much the question of "generation" was in play in the Gen Z protests. Much of the branding and optics are for international audiences even more than domestic ones, as counter-intuitive as this may seem at first. This is because the final call for 'regime change' comes from the leaders of the countries to which the protests were marketed globally. There is much potential, however, in going after the "Boomer" as a category in forthcoming global discord projects, similar to what we've seen in the U.S. May of '68 had many features of a Color Revolution, and the generational divisions were highlighted. But this works best if those divisions are expressed politically, and not within families.

"Boomer" carries different connotations outside the United States or the broader Western world compared with other countries that are more often the targets of color revolutions. Before the phrase 'Okay boomer' emerged, it had no connotation at all. Often, both in the U.S. and globally, it pertains to anyone over thirty or over forty, or anyone that a younger person aims it at. As American culture plays a less central role as a soft-power subtext in color revolutionary mass psychology, we see a deeper exploitation of more universal and enduring themes, like intergenerational conflict.

Weaponizing Generational Differences

Intergenerational divisions extend beyond policy into deeper questions about work, relationships, and what a meaningful life is supposed to look like. Surveys it shows that Baby boomers are broadly unpopular among those who came after them, with Dr. Lawrence Samuel writing in Psychology today in 2020:

"Because of these traits and having spent their formative years in what was unarguably a special time and place from a historical perspective, baby boomers believe they were and remain a kind of chosen people."

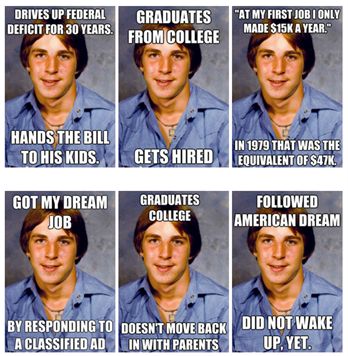

There are some real cultural reasons to dislike boomers, but the problem is also that we live in an era where the organicity of viral ideas are mixed with intentional corporate and intelligence driven projects. Memes attacking the boomer generation began to predominate as a theme, would tend to reflect a combination of real existing tensions which an intentional amplification by organized media.

The "Old Economy Steve" meme circa 2011

Reducing complex structural failures to the moral flaws of one age group turns them into a cultural scapegoat, and therefore becomes a convenient method for the powers that be.

Within the familiar toolkit of color revolution tactics, the exportation of intergenerational warfare can no doubt become an even greater effective instrument. Instead of mobilizing society against something concrete (which runs the risk of actually being addressed sufficiently), this irrational ageist approach turns age cohorts against one another, reframing economic and political failures as moral conflicts between generations, which are very hard to quantify and 'solve' in the conventional sense. Youth is encouraged to see itself as uniquely enlightened yet permanently cheated, while older cohorts are recast as hoarders of power and privilege, standing against fairness out of spite or senility. The result is a society busy litigating its own family arguments in public, expending emotional energy on blame rather than on institutional accountability. It is a subtle maneuver, because it draws on real grievances and authentic tensions, yet redirects them into a narrative that fragments solidarity and makes coordinated political action across age groups far more difficult.

While the boomers being blamed did not, in any meaningful sense, exercise determinative agency over the corporate decisions, Federal Reserve policies, or monetary frameworks that produced these outcomes, voices which could express these points are drowned out in the chorus of the boomer-blaming narrative. Boomers were largely just citizens living their lives, voting in ways that seemed to make sense at the time, often on issues where the consequences would not materialize for decades, and was based in assumptions about geopolitical outcomes that did not materialize. The one-to-one correlation presumed between what a voting bloc desired and what policy actually delivered has never been particularly robust.

A fundamental distinction in operationalization

"OK Boomer" contains tremendous power, and can be used in two distinct and virtually opposite ways, and also simultaneously. In one case, they can be used internally in a society to deflect blame from the real powers that be. This is how it is used in the U.S. The real powers behind the controlled elections, monetary policy, trade agreements, deindustrialization, borrowing against the future, and so on (which were the causes of decline in a society), can be virtually ignored, and the social consequences of these felt by each individual can instead be blamed on the culture and attitudes of a whole previous generation who were in more ways the product of the society more than they were its organized and coherent controllers. It is noteworthy here to consider the contradiction latent in most anti-boomer hysteria; most would agree societies are not as democratic as they profess to be and the disastrous policies attributed to the whole cohort were far more largely the result of the policies of the few in power. In the domestic iteration, the psychological operation is deployed domestically by that society's own ruling class in order to shift accountability to the elderly as an entire cohort.

However, as an export weapon, it must take on a different dimension, as seen in Paris in May of '68, which was really little more than a takedown of a Gaullism that was moving in the direction of a kind of Western Titoism, much to the chagrin of the emergent finance globalism of that day and age who wanted de Gaulle out. The type of long-term social project that emerged from Paris came to define the entire Western 'new left', until this very day. This is what we mean by long term soft-power and color revolutionary change over decades.

With something as paradigmatic to the collective West as the rise of the new left, we should note that it crosses into both spheres: it can be used to promote both blaming the whole prior generation to deflect from those in power, but also against those in power on the basis of their gerontocratic features.

Another important consideration mentioned at the start, but really framing our conclusion here, is the Baudrillardian aspect in this. Hyperreality is not only artificial, it replaces reality. What a majority or sizable number of people believe to be true is, politically speaking, the same as being true. It doesn't truly matter if the prior generation had it better or not, just as it doesn't matter that often that generation had little real agency in the decisions of finance and industry, simply because they voted every few years.

This is why hyperreality is such an important aspect to understand in color revolutions, which delves into questions of latent human irrationality or malleability. There are a number of interwoven themes touched on in this piece which require further development and specification.

But what has emerged so far is a greater call to look at how meaning itself is manufactured and redirected, and how the intergenerational strife technology is used differently depending on context. Intergenerational tension is real, persistent, and historically grounded, yet it is also remarkably easy to exaggerate, stylize, and weaponize when it serves broader strategic ends. The "OK Boomer" trope, whether deployed domestically or exported abroad, functions as an agent that dissolves complex questions of power, policy, and political economy into something emotional and endlessly repeatable. In doing so, it can shift attention away from institutions and toward identities, away from systems and toward age cohorts, or conversely, that same age-based criticism can be transformed into a criticism of institutions and social power itself.

That last part is precisely what makes it useful within the logic of color revolutions and long-term soft-power operations. The danger is not that natural generational differences exist, but that they can be weaponized into becoming the primary lens through which all dysfunction is understood. The Gen Z protests reflect both long term social and cultural change being pushed consciously by Western oligarchical big tech through social media, and also short term calls to action like the toppling of government. While intergenerational tension is likely being caused by this long term process, similar to how older mass media was used to effect similar starting over sixty years ago in the so-called first world, it is being expressed also as a call to action in an immediate and kinetic sense. The more subjective and hyperreal the themes or grievances of a color revolutionary movement are, the more difficult they are to mitigate. Intergenerational conflict is a particularly important trope within color revolution technologies because, once it is properly understood, it can be anticipated, rationalized, neutralized, and prevented from succeeding, which there becomes an important vector of future research.

Follow Joaquin Flores on Telegram @NewResistance or on X/Twitter @XoaquinFlores