By David Stockman

David Stockman's Contra Corner

January 31, 2026

When we referred to the Donald's cockamamie invasion of Venezuela, that's exactly what we meant.

Washington's War on Cocaine is already unnecessarily killing 20,000 Americans per year via adulterated cocaine and thousands more in the course of moving contraband product through violent criminal syndicates from Colombia to the USA retail streets. So bringing the US Navy, Air Force and CIA to a War on Drugs which should never, ever have been declared 55 years ago is the very height of folly.

Yet, that isn't all. We also have the alleged prize of Venezuela's 303 billion barrels of oil reserve. But that ain't nearly what its cracked up to be, either.

To hear the Donald and his minions tell about it, you'd think that someone discovered the equivalent of Saudi Arabia's legendary Ghawar field in the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela. Alas, nothing cold be further from the truth.

The Saudi Ghawar field, the largest ever discovered, was indeed a black gold mine. In terms of sheer reserve volume, the original petroleum liquids in place thanks to Mother Nature was in the range of 170 billion barrels. Approximately 95 billion barrels have already been lifted since production commenced in 1951, but since the Ghawar field is so naturally prolific the ultimate recovery ratio is estimated at about 75%.

That's because during geologic times oil migrated upward into anticlinal structures, preserving its lighter composition due to minimal biodegradation and favorable trapping mechanisms. Accordingly, the world's largest conventional oil field in terms of recoverable reserves encompasses just 8,400 square kilometers in eastern Saudi Arabia, and consists of lighter crude oils trapped in deep carbonate reservoirs from Jurassic-era limestone formations.

That is to say, figuratively speaking the Saudi's have merely needed to stick a straw in the ground in order to pump to the surface at low cost most of the oil deposited by Mother Nature over the course of the geologic ages. Consequently, after 75 years of oil essentially burbling to the surface owing to natural reservoir pressure-aided in recent decades by water injection-there are still 30 billion barrels of recoverable reserves left at today's technology and prices.

Needless to say, the Orinoco Belt in Venezuela represents the opposite extreme of geology and therefore cost of production. In contrast to Ghawar, the Orinoco Belt spans about about eight times more territory at about 55,000 square kilometers in eastern Venezuela, which areas contains vast accumulations of extra-heavy crude oil trapped in shallow, unconsolidated sandstone reservoirs.

These deposits formed from ancient marine sediments that underwent biodegradation over millions of years under shallow surface waters, resulted in highly viscous, dense oils with low mobility. Representative of Orinoco oils, Zuata crude has an API gravity of around 9 degrees, classifying it as extra-heavy, with a viscosity that makes it behave more like tar than liquid oil at room temperature.

The crucial economic point is this: Zuata's low gravity stems from the loss of lighter hydrocarbons through bacterial degradation in the reservoir, leaving behind heavier molecules rich in asphaltenes and resins. Hence, the metaphor of Mother Nature's thievery.

Ghawar's Arab Light crude, by comparison, boasts an API gravity of 33 degrees, making it medium-light and far more fluid. This higher gravity results from the field's deeper burial and isolation from surface waters, preventing significant degradation and retaining volatile components that enhance flow properties.

Likewise, the sulfur content further differentiates these deposits. Zuata oils contain about 2.5% sulfur by weight, earning them the "sour" label due to hydrogen sulfide and other sulfur compounds formed during maturation. The Orinoco's sulfur originates from organic-rich source rocks in a sulfate-rich environment, while Ghawar's lower content reflects cleaner carbonate sources.

In terms of reservoir size and original oil-in-place (OOIP), both fields are supergiants, but as indicated their estimated ultimate recoverability rate is vastly different. While the Orinoco's OOIP is estimated at over 1.3 trillion barrels, which gives rise to the image of massive reserves, only about 20-30% (@ 300 billion barrels) is deemed recoverable with current technology due to the oil's natural, stubborn immobility.

In short, Ghawar's high recovery rate and low extraction cost is due to its excellent permeability and natural drive mechanisms. These differences underscore Orinoco's "stranded" resource status versus Ghawar's prolific output. Accordingly, production processes for these fields diverge markedly due to their physical properties.

Ghawar benefits from natural reservoir pressure, allowing primary recovery through simple vertical wells where oil flows freely to the surface at low cost (under $5 per barrel in many cases). Production commenced in 1951, peaking at over 5 million barrels per day (mbpd) in the 1980s, sustained by water injection since the 1960s to maintain pressure. Current output is around 3.5-3.8 mbpd, managed for longevity.

Zuata production, starting in earnest in the 1990s, required high-cost advanced enhanced oil recovery (EOR) techniques from the outset. Steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD) or cyclic steam stimulation injects hot steam to heat the viscous oil, reducing viscosity for flow through horizontal wells. This energy-intensive process demands massive water and fuel inputs, with wells costing $10-20 million each versus Ghawar's $1-5 million.

Due to this far more energy and capital intensive production process, the Orinoco fields demand a high level of equipment maintenance and replacement. The socialist government's failure to make these investments has caused total output to plummet to under 1 mbpd, far below its 3 mbpd potential.

Post-extraction processing highlights further contrasts. Ghawar's light crude needs minimal treatment-basic separation of water and gas-at the wellhead before pipe-lining to refineries. Its natural pressure aids transport over long distances without dilution.

Zuata, however, must be heavily diluted with naphtha or lighter crudes (up to 30% by volume) to achieve pipeline-capable viscosity. That adds $10-15 per barrel in costs and requires dedicated upgraders to partially refine it into synthetic crude for export.

Finally, refining Ghawar's medium-light sour crude is straightforward in standard facilities, yielding high proportions of valuable products like gasoline and diesel after desulfurization. Refining costs average $7-10 per barrel, with simple hydrocracking sufficient.

Zuata's extra-heavy sour nature demands complex refineries with cokers and hydrotreaters to break down heavy residues, costing $12-15 per barrel or more. But that isn't all. Crucially, the refined product yield from the Zuata heavy crude is far inferior to that of Saudi light crude for the simple reason that every first year petroleum geology student knows, but apparently no one on the Trump administration ever bothered to check out.

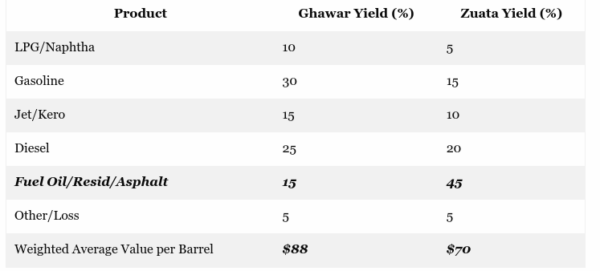

To wit, fully 45% of the refinery yield from Zuata heavy oil consists of low-value fuel oil, residual oils and asphalt, while the high-value light fraction yield (LPG/Naphtha, Gasoline, Jet/Kero) is just 30%. By contrast, the light fraction yield from the Ghawar crude is upwards of 55%, as shown in the table below.

In all, one barrel of crude at today's wholesale market prices yields $88 of petroleum products from the Ghawar crude oil, but just $70 from the Orinoco Belt heavy crude represented by the Zuata grade.

Mr. Market adds substantial cost premiums to convert Zuata heavy into saleable petroleum products. This includes the extra capital, steam, process chemicals, lifting equipment and diluents for pipeline transportation-and then another set of heavy duty cost penalties for extracting high value light petroleum products from the heavy hydrocarbon molecular chains contained in the Zuata heavy oil and various other grade extracted from the Orinoco Belt.

Needless to say, if it costs a whole lot more to produce and yields a goodly amount less revenue from refined products in the market place, the two commodities at issue here are similar only in that they are called "crude oil." In the real world, they are actually miles apart when it comes to economics.

So there will be no bonanza-even if the Trumpian cowboys succeed in stealing oil from the sovereign state of Venezuela. But even more pointedly, the argument that we need to start a war so that China doesn't get the privilege of loosing its shirt in the Orinoco petroleum swamp is downright ludicrous.

Reprinted with permission from David Stockman's Contra Corner.